Learning the art of implementation science

Across Canada, Can-SOLVE CKD research is improving the health of people living with kidney disease.

This includes efforts to improve living donor kidney health transplantation, support self-management of kidney disease, and enhance kidney health screening in rural and remote Indigenous communities – all of which have been introduced at the provincial level.

As we move into our second phase (2022-2027), our focus shifts to implementing these and other innovations into health care policy and practice on a wider scale.

Of course, this is easier said than done. Implementation science, as the process is known, is a highly strategic process encompassing many different frameworks.

In this issue of The Kidney Quarterly, we explore the how, what, and why of implementation by looking at examples from across Can-SOLVE CKD.

To receive The Kidney Quarterly and other updates from the Can-SOLVE CKD Network, subscribe to our mailing list.

Implementation Science

Implementation science helps overcome barriers to change

While it may sound simple, moving new research evidence into health care practice is rarely straightforward. Implementation science, as the process is known, involves a lot of strategy and careful planning.

“Implementation science was really developed and came out of the fact that people were producing evidence-based practices, and assumed that if they built it, people would just come and use these [tools]. And that is not the reality,” explains Julia Moore, the Executive Director at the Center for Implementation.

She notes that changing people’s behaviour is often challenging, regardless of what the behaviour might be. Many people know that exercise and eating healthy are important but still struggle to adopt lifestyle changes. The same is true for individuals in health care settings who face barriers to incorporating new evidence-based practice into their workflow.

The types of barriers can vary, Moore notes. Some people may not see the benefits of the change or may lack confidence in their ability to implement it.

Additional barriers exist at an organizational or even systems level. “You may have people who are motivated to change and want to do something differently, but they work at an organization that is not set up to make that happen easily,” explains Moore.

The good news, she says, is that the process for implementing new evidence into practice is always the same, regardless of which barriers exist. The key is to identify who is being asked to do something differently, and to identify the barriers and facilitators at an individual, organizational, or systems level. “[My colleagues and I work] in dozens of countries around the world and it doesn’t matter if you are working in Uganda or Alberta – that process can still get you there, even if the barriers are different,” emphasizes Moore.

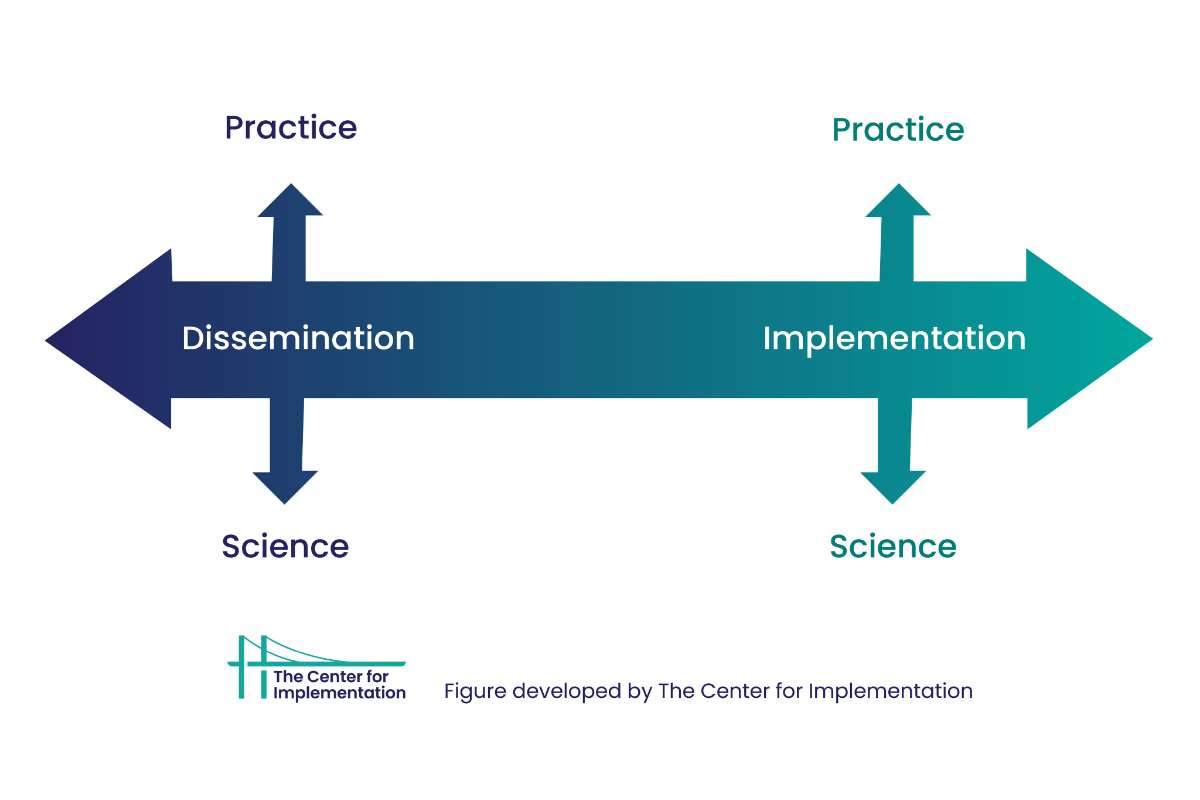

Figure identifies difference between Implementation Practice and Implementation Science and Dissemination.

To support Can-SOLVE CKD in its implementation phase, Moore gave a two-part interactive workshop on implementation science to network members this past July, and shared access to an online course, StrategEase: The how of creating sustainable change (an online course). Equipped with new skills and resources, Can-SOLVE CKD members are beginning to outline unique implementation strategies for each of their projects.

Susan McKenzie is a patient partner co-leading Can-SOLVE CKD’s living kidney donor research program. She points to the example of the Transplant Ambassador Program (TAP), an initiative that has grown out of the research program and generated new knowledge for improving organ transplantation in Canada.

“Our goal now is to look at how we can put this information together, so it’s concise and meaningful, and focus on which audience [we want to target],” explains Mckenzie.

The team is planning to implement scorecards at hospitals to evaluate the efficiency of transplant processes. But McKenzie recognizes that more effort is needed beyond handing out the scorecards.

McKenzie says she expects change to be slow, which can be frustrating for some patients, but emphasizes the need for patient partners and everyone involved in research projects to be persistent. “We aren’t just suggesting ideas that may or may not have impact – these are published best practices that will save lives,” she says.

While implementation science can be a slow process – especially for patients who are eager to see better kidney care – Moore says she has a positive outlook on the current state of implementation science.

“I think it is an unbelievably exciting time for people to be in this space of wanting to implement things and create impact, because we are seeing momentum at every level of the system for this – interest from funders, policy-makers, philanthropic groups, health systems, and even clinicians and people on the ground who want to support implementation,” explains Moore. “I’ve been in this space for 15 years and it has never felt less lonely than it has right now.”

“Just having the scorecard doesn’t mean anything if people don’t know if it exists or care that it exists, or don’t have the [means] to implement it. So for us patient partners, I think that we can bring more attention to the challenges we as patients face within the current system in order to create positive change.”

Susan McKenzie

Patient Partner, Can-SOLVE CKD

Implementation Science

New tool offers a smoother pathway to implementing research

Can-SOLVE CKD Phase 2 is focused on translating research findings into clinical practice, and the network’s Knowledge User/Knowledge Translation Committee has wasted no time creating new tools to support this effort.

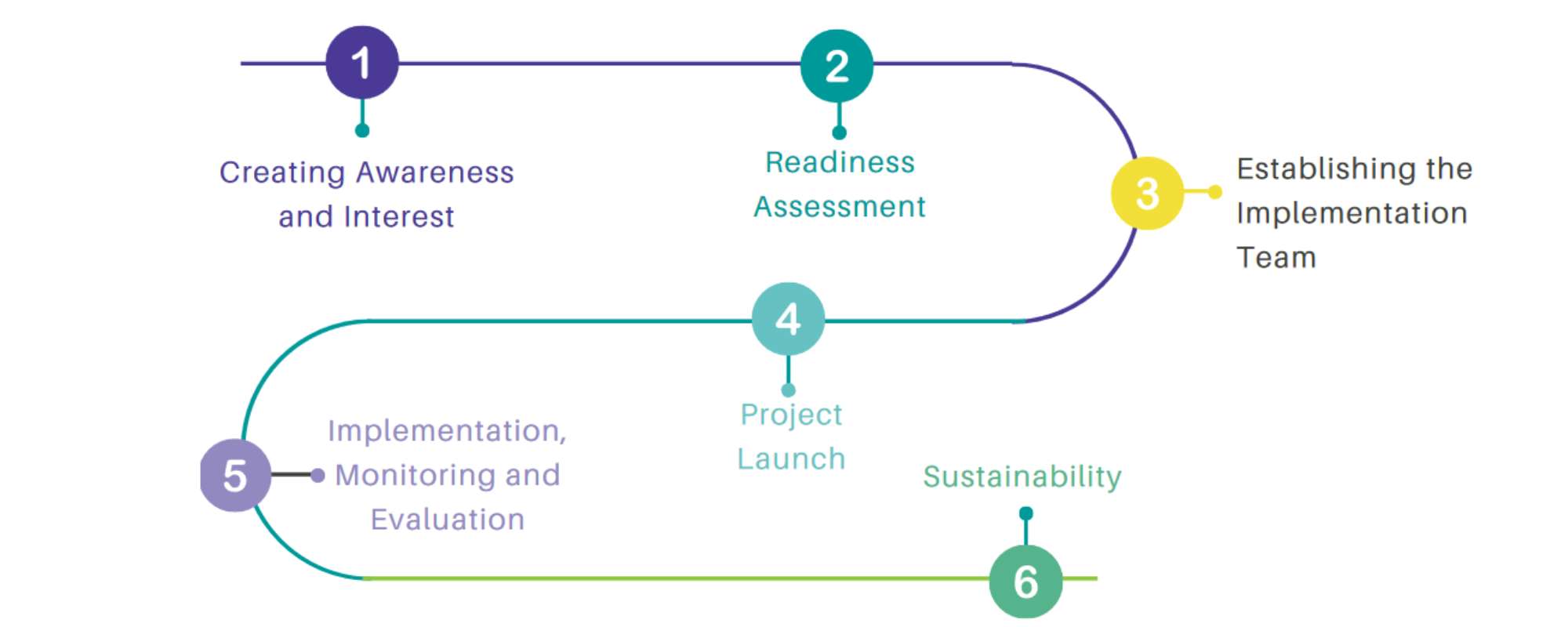

The committee’s new “Pathway to Implementation” document outlines a six-step process to guide research teams as they work to implement and scale up their innovative research. It helps research teams identify target users and delegate roles during the implementation phase. Team members are encouraged to consider how the intervention can be monitored, sustained, and evaluated.

The KU/KT Committee has also created an Implementation Toolkit, which offers research teams a suite of planning documents and links to resources to guide their work.

“The pathway document and the Toolkit contain a large amount of information to support the projects, and help them identify other resources they may need for successful project completion],” explains Dr. Steven Soroka, co-chair of the KU/KT Committee, who helped lead the development of the Pathway to Implementation and accompanying Implementation Toolkit.

Image of Implementation Pathway

Importantly, while each research team must develop unique implementation strategies for their project, the Pathway to Implementation provides general guidance and resources that are applicable to all teams.

After each team has used the pathway and toolkit, they should have a collection of guiding documents that other teams can use to implement similar projects in other regions of Canada. Soroka hopes the Pathway to Implementation will help project teams participating in Can-SOLVE CKD Phase 2, as well as research teams from Phase 1 that are wrapping up their projects.

Importantly, the pathway and toolkit were created with feedback from implementation experts, patient partners, and other stakeholders.

“We really we enjoyed working together,” says Allu. “Even though we come with different ideas and backgrounds, we were able to create something really useful in a short time.”

If you are interested in an upcoming session “How to plan for implementation; practical tips and a project example of how you can use a 6-step “Pathway to Implementation” guide” on February 9, please register:

https://us06web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZItcuyhqT8vHtRRXSn6J3Rsq0wOkBIqS1Vf

For more information about the tool, please contact Selina Allu soallu@ucalgary.ca

Note: The tool will be available on our Can-SOLVE CKD website (https://cansolveckd.ca/resources/training-modules/) by Feb 2023.

“Because every project is different, the pathway document isn’t meant to be prescriptive. Rather, we’re thinking of this document as something that would help project teams think about the different processes, the different activities, what artifacts they may need at different stages, and their implementation process.”

Selina Allu

KT broker and implementation support practitioner supporting the KU/KT Committee

Research Project

The implementation of APPROACH projects sees positive results

Cardiac catheterization and intervention procedures are important for diagnosing and treating heart conditions. However, some people are at high risk of kidney injury from the procedures, which can present challenges for those living with CKD.

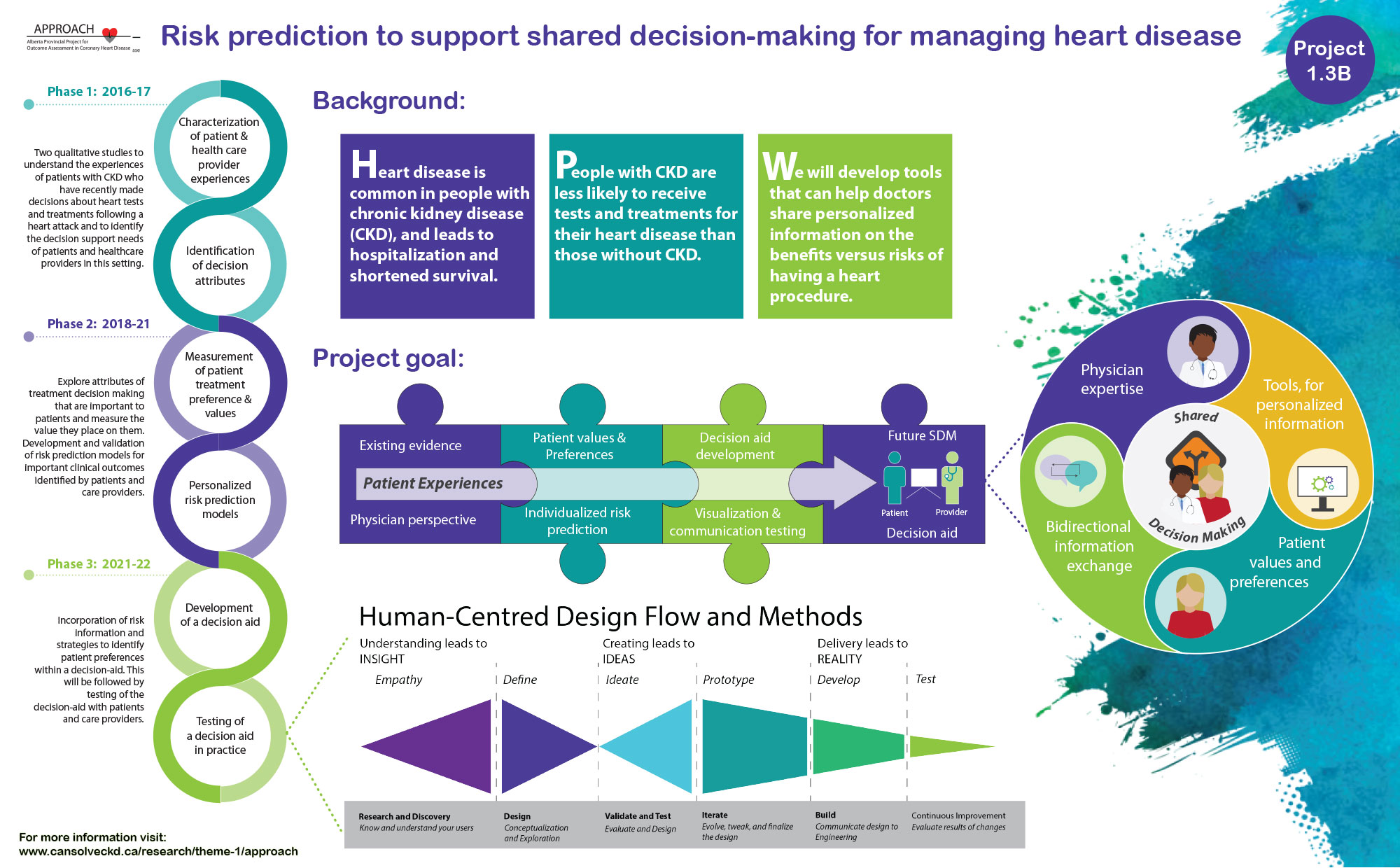

To lower the chances of this happening, Dr. Matthew James, an Associate Professor and Clinician Scientist at the University of Calgary, and other members of the APPROACH team, implemented a decision aid tool to support cardiology teams in identifying patients at high risk of kidney injury and taking steps to reduce kidney disease following the procedure.

Once a high-risk patient is identified using the tool, special steps can be taken to lower the amount of contrast dye used during the procedure and to maintain adequate fluid levels throughout.

This past September, the APPROACH team reported that their strategic intervention resulted in a significant decrease in the number of patients who incur kidney damage from the procedure – by about 30 percent – following the project’s implementation across Alberta.

James notes several factors contributing to the project’s success, including the introduction of a decision support tool into practice at the point of care.

“It’s hard to accurately estimate the risk for each individual patient encountered and tailor their care appropriately to make a procedure as safe as possible for each person,” explains James. “The introduction of these decision support tools provides health care teams with this information right at the time they need it to make a decision about how to perform a patient’s procedure.”

Importantly, the APPROACH team also provided care teams with feedback on their progress every three months, so medical staff could see the impact of their care processes over time. James says other factors supporting the project include data collected through a unique electronic health information system and collaboration among the different care team members. For example, nurses were responsible for completing risk models and identifying patients at risk of kidney disease, while radiology technicians notified the care team about safe contrast dye levels and reported when these levels were approached. Physician champions at each centre also helped drive change, James says.

Data were collected over the course of the study to evaluate its effectiveness, capturing the outcomes of more than 7,000 patients receiving heart procedures across Alberta who were identified as high-risk for kidney disease following procedures.

“These results were really exciting for us because they showed that the project achieved its goals,” says James.

The APPROACH team was also concerned that the intervention could create anxiety for patients learning about the risks associated with their heart procedures. “But reassuringly, evaluation of the patient experience showed that this didn’t seem to be the case,” James notes.

“Most patients were actually quite pleased to hear there was attention being paid to this and there was a clear follow-up plan for them as part of the project – how they were going to get their kidney function tested afterwards, and how their family doctor would receive information on what to do if there were kidney problems.”

On a personal level, James says that working on this project has been very rewarding. “It provided our team with practical experience related to the principles of implementation science,” he explains. “There are many theories and frameworks related to implementation of this kind of change, but actually working through a project like this really makes you understand what those aspects are getting at and why they are important.”

Through Can-SOLVE CKD, the APPROACH team is working to ensure the project is sustainable and to scale up work in this area. They are creating additional tools that support shared decision-making between patients with CKD and doctors when making decisions related to the use of these heart procedures.

We are working to implement these types of decision support tools more broadly in our next phase of work. So we are working on developing collaborations with other centres across Canada where’s there’s interest in implementing and evaluating these types of tools for the care of heart disease for people with CKD."

Dr. Matthew James

Clinician Scientist

Hemodialysis

Finding out what does – or doesn’t – help dialysis patients

Can-SOLVE CKD research teams are investigating new strategies to improve care for people living with kidney disease, including improvements in how hemodialysis is offered. Currently, hemodialysis is one of the most common life-sustaining treatments for people with kidney failure. However, it can strain the body, and patients receiving hemodialysis frequently die from cardiovascular disease.

Previous evidence has suggested that using dialyzer fluid at temperatures slightly below patients’ natural body temperature may help reduce these negative cardiovascular effects. A research team led by Can-SOLVE CKD investigator Dr. Amit Garg, a nephrologist at the London Health Sciences Centre and Professor at Western University, decided to investigate this possibility in more detail.

To do so, they launched MyTEMP, a large-scale randomized clinical trial across 84 dialysis units in Ontario. Whereas many kidney patients are excluded from clinical trials, this study provided an opportunity to study an intervention with more than 15,000 patients from across Ontario.

In the study, some of the participants received their dialysis with dialyzer fluid that was a standard temperature of 36.5°C, while other participants received treatment with fluid that was 0.5°C below their individual body temperature, as measured prior to starting dialysis.

The results, published in the Lancet, show that the intervention (lower temperature of dialyzer fluid) does not improve cardiovascular events in dialysis patients, and may add to their discomfort while receiving dialysis.

“Based on the trial’s findings, dialysis centres that are currently providing cooler dialysate as a centre-wide policy should consider using a dialysate temperature of 36.5°C as their standard for the comfort of their patients,” says Garg. He notes that dialysis clinics increasingly use cooler dialyzer fluid, despite the lack of evidence supporting the practice.

Garg adds that if Can-SOLVE CKD and other research programs are to truly transform kidney care in Canada, it is important to not only identify new therapies that are effective or beneficial, but rule out what doesn’t work.

“What’s remarkable about the MyTEMP trial is the methods we used. Because we embedded the trial into existing healthcare at nearly all hemodialysis centres in Ontario, we were able to determine whether the intervention would improve outcomes in a real-world setting that represented all patients who receive hemodialysis in routine care."

Dr. Amit Garg

Nephrologist

Connect with us!

Subscribe to learn more about what we do, why it matters, and how you can get involved!